Was there really ever a Golden Age? For at least one sector of French society, the period between 1871 and 1914 known as France’s Belle Époque was precisely that: a time when life brimmed with possibilities and the future sparkled with promise. The era began in late 1871, a turbulent year whose events had scarred the French psyche deeply. In the wake of a humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the once-proud nation found itself compelled to quash by force the uprising of the Paris Commune, which had threatened to escalate into full-blown civil war.

After having lived through such upheaval, it’s little wonder that as the country returned to peace and stability, those able to benefit from the resulting prosperity viewed the future with renewed optimism. Soon the upbeat mood of privileged city dwellers found expression in exuberant forms of fashion and entertainment. It’s not by chance that haute couture originated in Paris, which each year revealed eagerly awaited new fashions, or that restaurants such as Maxim’s rose to prominence as chic night spots where wealthy socialites would gather, dine and simply be seen.

The Palace That Outshone Them All

Large public buildings throughout Europe already provided glamorous settings for theatre, concert and opera performances: opulent Baroque or neo-Renaissance style creations whose interiors employed extravagant gilded and trompe l’œil decoration designed to impress. All were upstaged, however, when le Nouvel Opéra de Paris opened in 1875, at the very height of the Belle Époque. Constructed for Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, it soon became known popularly as le Palais Garnier, after its architect Charles Garnier (who also designed le Casino Opéra de Monte-Carlo). Wealthy Parisians, overawed by its dazzling splendour from the moment they entered the Versailles-like grand foyer, fell instantly in love with what had effectively given them a palatial setting of their very own.

Not surprisingly, la Ville-Lumière’s plentiful financial rewards and growing sense of joie de vivre somehow failed to filter down to brighten the lives of those who continued to toil for a pittance on the land or down in the mines. However, before long many of those poised between the two extremes in the provinces found themselves able to embrace at least some of the upbeat mood and gaiety of the Belle Époque.

Provincial France Joins the Party

Soon neglected, down-at-heel bars, cafés and restaurants were enjoying a new lease of life by being redecorated in the bright, fashionable taste of the period. Then as now, the heady cocktail of alcohol and merriment got people in the mood to dance, so the tavern-style guinguettes which had sprung up in and around Paris to provide cheap drinks, lively music and a dance floor soon began to appear elsewhere.

Les guinguettes of Paris were responsible for spawning a whole new genre of popular music. Bal-musette took its name from la musette, a bagpipe-style wind instrument which had been popular in the Auvergne, and which really took off in the capital during the 1890s in the hands of accomplished Auvergnat musicians recruited to play in the bars and restaurants opened by their enterprising compatriots.

When Music Sparked Riots

For the next forty years or so la musette would remain unchallenged as the instrument of choice for social gatherings, but began to fall rapidly out of favour when another previously little-known import from the Auvergne put in an appearance. This time it was the turn of the accordion, whose already big sound was more than capable of holding its own in the company of guitars, a double-bass and drums, creating an infectious wall of sound which dancers found irresistible.

However, not everyone was quite so ready to abandon their allegiance to la musette. As dissent between rival aficionados became increasingly heated, things eventually moved from merely vocal to physical, and violent fights began to break out. To maintain public order, the Parisian chief of police therefore outlawed all bals populaires throughout the city, with the result that many of the guinguettes decided to relocate, notably to the riverbanks of the Seine and Marne.

Happily, their faithful clientèle continued to support them and attend events, their numbers boosted by newcomers from Spain, Poland, Argentina, the USA and elsewhere, along with their respective musical influences. Before long those on the dance floors were embracing imported genres like the polka, the mazurka, the fox-trot, the tango, the cha-cha, the paso-doble, the rumba and eventually the java (a slightly risqué fast waltz variant). In what was clearly something of a social and ethnic melting pot, a good time was nevertheless, by all accounts, had by all.

Montmartre’s Bohemian Allure

Meanwhile, those with more Bohemian lifestyles were finding their own entertainment in the cabarets of Montmartre, in those days a cheap and distinctly louche hilltop shanty community but one which attracted and inspired great artists including Picasso, Degas, Matisse, Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. Among the most popular night spots were Le Chat Noir and Le Moulin de la Galette, a working class dance hall celebrated on canvas by Renoir, Picasso and others.

Soon the area’s reputation for lively, often raucous cabarets and café-concerts spread, social boundaries became blurred and Montmartre became a focus for just about anyone looking for escapist entertainment. Catering for those slightly higher up the social scale was the Moulin Rouge, which opened in 1889 and staged all manner of increasingly exotic shows, many of which were observed and portrayed in the now familiar graphic imagery of regulars such as Seurat and particularly Toulouse-Lautrec.

By the time the 19th century was drawing to a close, Montmartre boasted around forty nightspots, although its very popularity had inevitably shifted the area’s original appeal as an alternative, even subversive haunt to merely a popular centre for more mainstream entertainment, something freely available to almost anyone living in a city or large town.

Art Nouveau’s Swirling Revolution

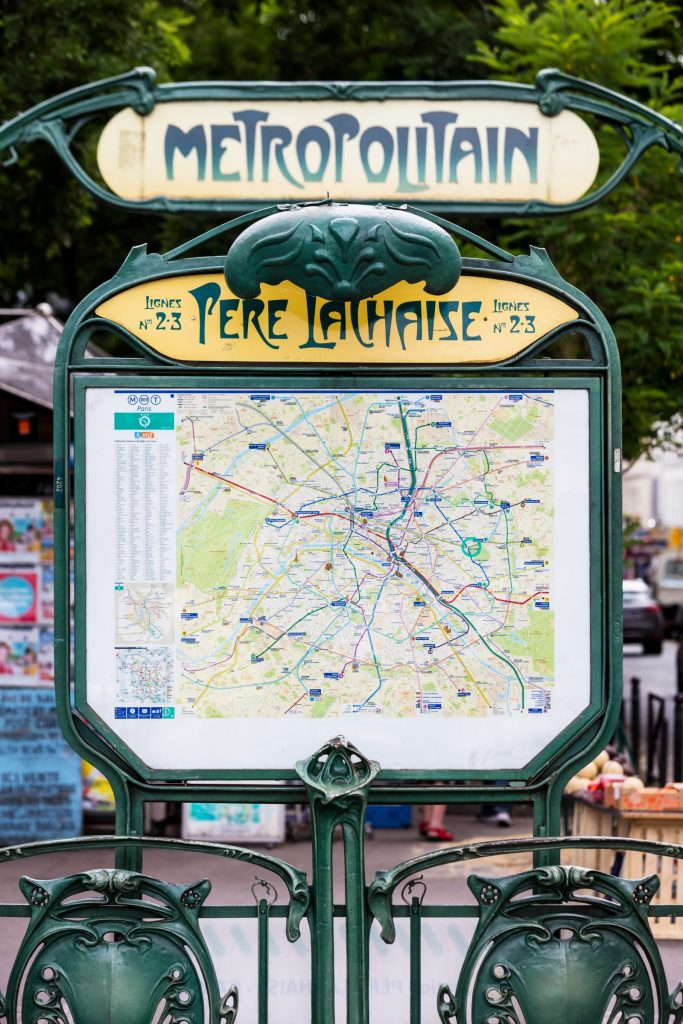

As the good times continued, their effects were expressed in the swirling imagery of Art Nouveau, which was employed to sensational effect both in France and elsewhere by a host of creative artists, architects, furniture designers, glass makers, illustrators, jewellers and sculptors. Before long the style had become omnipresent in everyday life, appearing on colourful painted publicity murals, in printed media and even Hector Guimard’s fantastic entrances to the Paris Métropolitaine, whose distinctive typefaces he also styled.

While traditionalists criticised them as being ‘non-French’, others including Salvador Dalí (who considered them ‘divine’) were more enthusiastic, and the 80-plus surviving examples now enjoy Monument Historique protection.

The Exhibition That Crowned an Era

Guimard had actually received his commission as part of preparations for the capital’s vast Exposition Universelle, which was due to open in 1900, and whose main attraction would be the Tour Eiffel, retained from its sensational debut at the previous year’s event. Visitors to the 1900 Paris Exhibition would have been awe-struck by such wonders as pavilions and whole villages showcasing the colonies and other nations, a 110-metre big wheel, moving walkways, electric tramways and trolleybuses, motion pictures, theatre and of course music halls.

It was a fitting climax to an era filled with upbeat optimism and creative expression, and which would continue to flourish until ending abruptly with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The world would never be quite the same, but the legacy has since become known as ‘La Belle Époque’ and continues to infuse the romantic global image of ‘La Belle France’.

Allow several days to explore Belle Époque Paris properly, or seek out the architectural legacy in towns and cities across France, from Nantes to Orléans, Arcachon to Châtellerault, where the era’s distinctive decorative flourishes still grace everyday buildings.

Best Places to Experience It: Le Palais Garnier in Paris offers guided tours daily (€15 in 2026, booking essential via operadeparis.fr). For Belle Époque architecture without the crowds, explore Vichy in the Auvergne region, where elegant spa buildings and pavilions line the riverside parks.

Art and History: The Musée d’Orsay in Paris, housed in a Belle Époque railway station, showcases the era’s artistic output including Toulouse-Lautrec’s cabaret posters and Impressionist masterpieces. Open Tuesday to Sunday, 9.30am-6pm (Thursdays until 9.45pm), €16 in 2026.

Dancing Then and Now: A handful of traditional guinguettes still operate along the Marne riverbanks east of Paris from May to September, offering riverside dining and dancing to accordion music on summer evenings. Chez Gégène in Joinville-le-Pont is the most famous.

Combine Your Visit: The Musée Carnavalet in Paris’s Marais district includes recreated Belle Époque interiors and is free to visit. It’s a 20-minute walk from the Opéra Garnier.

Hidden Gem: Seek out surviving Art Nouveau shopfronts throughout Paris and provincial cities. The ornate ceramics, ironwork and stained glass remain on working shops and restaurants, bringing colour to everyday streetscapes over a century later.

This article was first written for Living Magazine by Roger Moss and has been edited for Savvy France.